Hyperboloidal Holography

Hyperboloidal slices are hyperbolic manifolds. Can we use them to establish holography for isolated systems?

Brief History of Bekenstein-Hawking Black-Hole Entropy

When physicists want to understand something, they consider idealizations and extremes. To understand spacetime then, consider black holes.

The black holes of nature are the most perfect macroscopic objects there are in the universe: the only elements in their construction are our concepts of space and time.

Chandrasekhar (1983)

Black holes are simple with just two properties: mass and rotation. By dropping an object into a black hole, you can increase its mass and change its rotation.

The simplicity of black holes contradicts the second law of thermodynamics, which states that total entropy never decreases. If black holes are that simple, you can reduce total entropy by dropping a high-entropy object, say a hot teacup, into the black hole.

Wheeler, best known for coining the term “black hole,” tasked one of his graduate students at Princeton, the young Bekenstein, with resolving this paradox. The golden age of relativity was in full swing around 1970, and Princeton was among the best places to be. Christodoulou, another student of Wheeler, and Hawking had just shown that the area of a black hole horizon never decreases. To resolve the entropy paradox, Bekenstein conjectured that black holes must have entropy and that the entropy must be proportional to the area of the black hole horizon in Planck units. The proportionality constant was determined by the discovery of Hawking temperature, which is why we call it the Bekenstein-Hawking Black-Hole entropy $$ S_{BH} = \frac{A}{4 L_P^2}$$ where $A$ is the horizon area, $L_P$ is the Planck length, $S$ stands for entropy (probably after Sadi Carnot), and BH stands for Brief History.

You may think this is a curious result about curious objects called black holes with little relevance to our notion of spacetime. But consider the following question: what is the maximum entropy in a finite, say spherical region? If you take some high-entropy matter and squeeze it spherically (with your mind), eventually, you hit the Bekenstein-Hawking entropy, and the compressed matter forms a black hole. This thought experiment leads to the surprising conclusion that the entropy of any matter system is bound by the surface area of the smallest sphere that encloses it1.

We started with black holes and arrived at the

Holographic Principle

Counterintuitively, the maximal entropy of a region scales with the area of its boundary, not its volume. The holographic principle pushes this area-dependence further, suggesting that the dynamics in a volume of space is encoded on the boundary of that space. In other words, the information content of a spacetime region is encoded on the surface of that region.

Take a break and think about this for a moment. How can our three-dimensional world be encoded on a two-dimensional surface? What does it mean? Is the universe a game running on the screen of an alien child? Are we trapped in The Matrix? Are we Livin’ on the Edge?

AdS/CFT correspondence

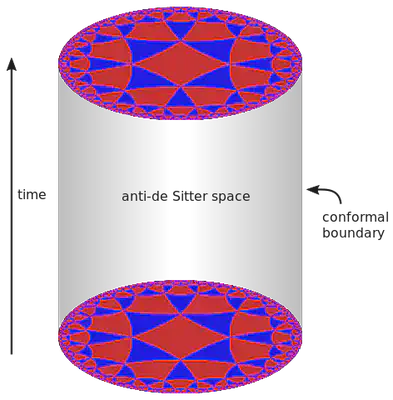

The most famous realization of the holographic principle is the AdS/CFT correspondence. Conjectured by Maldacena in 1997, the correspondence suggests an equivalence between a string theory in curved anti-de Sitter spacetime (AdS) and a strongly coupled conformal field theory in a lower-dimensional flat spacetime. Aside from the details, the remarkable aspect of the conjecture is the duality between the bulk and the boundary of AdS.

Below is a visual image for the AdS$_3$/CFT$_2$ correspondence. The cylinder represents the three-dimensional AdS$_3$ spacetime. On the boundary of the cylinder lives the 1+1 dimensional CFT$_2$. Slices of constant time are hyperbolic manifolds with negative curvature, drawn as Poincaré disks. A gravity theory within the disks is dual to a gravity-free theory on the bounding circle. The boundary of space encodes the bulk.

The negative curvature of AdS is a feature and a bug. It allows the realization of the holographic principle due to its hyperbolic slices, but it also makes AdS an unphysical model for our universe. At cosmological scales, the universe has positive curvature and resembles de Sitter space. At astrophysical and smaller scales, isolated systems are modeled by asymptotically flat spacetimes. Either way, anti-de Sitter spacetime, with all its bizarre features, is not a good model for physical reality.

Can we establish the holographic principle for isolated systems?

Hyperbolic Hyperboloidal

Consider the AdS$_3$ metric in static coordinates with curvature scale $L$ $$ ds^2_{\rm{AdS}} = - \left(L^2+r^2\right) d\tau^2 + \textcolor{RedViolet}{\frac{L^2}{L^2+r^2} dr^2 + r^2 d\theta^2},$$ Slices of constant time are hyperbolic spaces with negative curvature. Hyperbolic geometry has much more space near its conformal boundary than Euclidean space. It seems that flat spacetime with its Euclidean time slices and vanishing curvature would not allow such a description $$ ds^2_{\rm{Mink}} = -dt^2 + dr^2 + r^2 d\theta^2 . $$

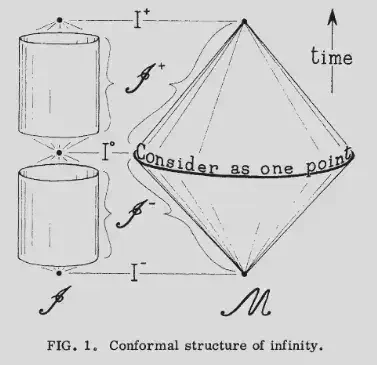

But now consider the time-shifted spacetime hyperboloid with curvature radius $L$ $$ (\tau-t)^2 - r^2 = L^2 $$ This hypersurface is spacelike everywhere and extends to null infinity. Such surfaces are called hyperboloidal. Solving for $\tau$, we choose the negative square root, so the surfaces extend to future null infinity. $$ \tau = t - \sqrt{L^2+r^2}.$$ In this hyperboloidal time, Minkowski metric has hyperbolic spatial slices $$ ds^2_{\rm{Mink}} = -d\tau^2 - \frac{2 r}{\sqrt{L^2+r^2}} d\tau dr + \textcolor{RedViolet}{\frac{L^2}{L^2+r^2} dr^2 + r^2 d\theta^2}. $$ Just like AdS, flat spacetime takes the form of hyperbolic space with a time direction. You can draw the spacetime geometry as a cylinder, which is what Penrose did in his first publication on conformal infinity in 1963.

The agreement of the geometry of hyperboloidal and AdS slices is suggestive. Calculations in the AdS/CFT literature performed on time slices may carry over to flat spacetime in hyperboloidal coordinates. One such example is the Ryu-Takayanagi conjecture.

RT if you agree

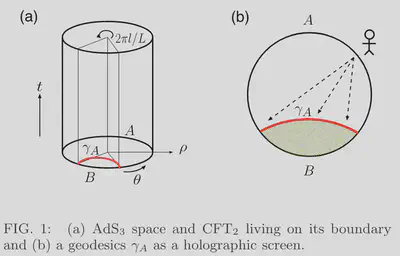

Ryu and Takayanagi (RT) have proposed a relation between geometry in AdS and entropy in CFT.

One can interpret the Bekenstein-Hawking entropy as a measure of information lost to external observers. The black-hole horizon acts as a screen dividing space into two subsystems inside and outside the horizon. Entanglement entropy is proportional to the area of this screen. The RT conjecture relates the entanglement entropy on CFT to the surface area of a screen in AdS that divides the AdS boundary into subdomains.

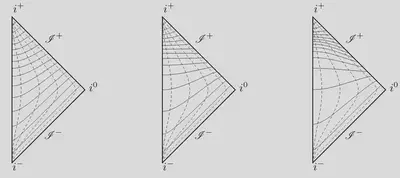

Words don’t do it justice, so let’s look at a picture. Below is a diagram from the RT paper for AdS$_3$ /CFT$_2$.

The two subsystems $A$ and $B$ of CFT$_2$ live on the boundary of AdS$_3$. They are separated by a screen $\gamma_A$ required to be an extremal surface in the bulk AdS$_3$. An extremal “surface” on a slice of AdS$_3$ is a geodesic line connecting the meeting points of the domains $A$ and $B$ on the bounding circle. The RT proposal states that the entanglement entropy of subsystem $A$ is proportional to the area of the screen $\gamma_A$: $$ S_A \sim \rm{Area\ of\ }\gamma_A $$ In this case, we are talking about the length of a geodesic on a time slice. You can easily see that the calculation does not change whether you are in AdS or hyperboloidal Minkowski. In the example on Wikipedia, the AdS$_3$ metric is written in the spatial coordinate $\rho$ defined through $r=\sinh \rho$, so $$ ds^2_{\rm{AdS}} = -\cosh^2\rho\ d\tau^2 + \textcolor{Blue}{d\rho^2 + \sinh^2\rho\ d\theta^2}. $$ The same spatial geometry is obtained in hyperboloidal coordinates in Minkowski2 $$ ds^2_{\rm{Mink}} = -d\tau^2 - \sinh\rho\ d\tau d\rho + \textcolor{Blue}{d\rho^2 + \sinh^2\rho\ d\theta^2}. $$ This flat metric describes a stack of hyperbolic disks, just like the AdS metric. The length of the geodesic and its relation to entanglement entropy are the same in hyperboloidal coordinates. The original RT proposal applies directly to flat spacetime!

The RT proposal reveals an interesting interpretation for the area dependence of entropy. It is easier to understand that entanglement entropy should be proportional to the area of a screen and not to the volume behind it. But maybe we should ask first: What is volume?

Thinking outside the ball

When we think of volume, we typically envision a box or a ball and consider the space inside. Relativity modifies our intuition about space and time, so it is reasonable that our notion of volume is modified as well. The volume of a region $B$ is the integral of the volume form $$ V_B = \int_{B} \sqrt{\det h} \ d\Sigma, $$ and depends on the spatial metric $h$. In flat space we have $\sqrt{\det h} =$ $r^2 \sin\theta$. The volume of a ball of radius $R$ gives us the usual formula that we memorize at school $$ V_{B(R)} = \int_{0}^{R} \int_0^{\pi} \int_0^{2 \pi} r^2 \sin\theta \ dr d\theta d\varphi= 4\pi \int_{0}^{R} r^2 dr = \frac{4\pi}{3}R^3. $$ For the hyperboloidal foliation with $L=1$ we have $$ h = \frac{1}{1+r^2}dr^2 + r^2 d\theta^2 + r^2 \sin^2\theta d\varphi^2,\quad \sqrt{\det h} = \frac{r^2 \sin\theta}{\sqrt{1+r^2}}. $$ The volume expression changes to $$ V_{B(R)} = 4\pi \int_{0}^{R} \frac{r^2}{\sqrt{1+r^2}} dr. $$ We can get a sense for it using Taylor expansions. For small spheres with $R \ll 1$, we get the usual result $$ V_{B(R)}=\frac{4\pi}{3}R^3+O(R^5).$$ For large spheres, however, the series expansion for $R\gg 1$ gives $$ V_{B(R)}=2\pi R^2 + O(\ln R).$$ Remarkably, volume and area scale the same way near the asymptotic boundary in hyperboloidal coordinates.

These are suggestive observations about the potential usefulness of hyperboloidal surfaces in holography. And indeed, there is a current effort using hyperboloidal surfaces for holography.

Celestial Holography

In the context of quantum gravity, the holographic principle suggests duality between a gravity theory in the bulk and a quantum theory on the boundary. Celestial holography suggests that asymptotically flat spacetimes are dual to a theory living on the “celestial sphere” at infinity.

The theory uses Bondi coordinates along null infinity to discuss asymptotic symmetries, and switches to a hyperboloidal slicing to discuss massive particles. The slices they use have been first proposed as a cosmological model by Milne in 1935. Milne slices are level sets of $$ \tau^2 = t^2 - r^2.$$ Introducing the spatial coordinate $$ \rho = \frac{r}{\sqrt{t^2-r^2}}, $$ the Minkowski metric takes the form $$ ds^2_{\rm{Mink}} = -d\tau^2 + \tau^2 \left( \textcolor{RedViolet}{\frac{1}{1+\rho^2} d\rho^2 + \rho^2 d\sigma^2}\right). $$ Again, we recognize the representation of Minkowski spacetime as a stack of hyperbolic disks. But in this case, the metric coefficients depend on time $\tau$. And the mean extrinsic curvature of Milne slices vanishes asymptotically in time as $K=3/\tau$.

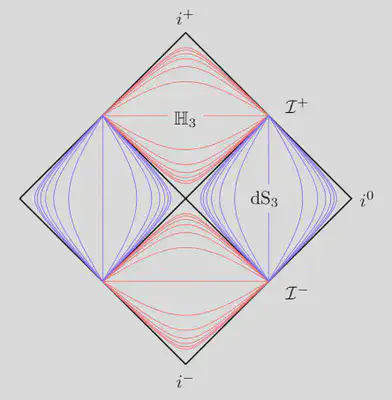

I suspect that the hyperboloidal foliation we discussed above is better than Milne slicing for holography. Consider the Penrose diagram of Milne slices.

- The slices intersect at null infinity.

- The coordinates are time-dependent.

- There is no analog of the AdS curvature scale.

In contrast, the hyperboloidal foliation has constant mean curvature, $K=3/L$, playing the same role as the curvature scale in AdS geometry. The coordinates are independent of time and provide a smooth foliation of null infinity. Below are Penrose diagrams for such hyperboloidal, constant-mean-curvature foliations with different values of the mean extrinsic curvature, which acts as a dial between characteristic and Cauchy surfaces.

Milne coordinates have one advantage that a hyperboloidal foliation of null infinity cannot provide. A massive particle in constant motion will asymptote to a point on the Milne slices. Dirac used this property in his 1949 paper on Forms of Relativistic Dynamics and it appears repeatedly in celestial holography. I’m not sure how important this is. But Milne coordinates are also hyperboloidal. So in that sense, celestial holography is already using hyperboloidal holography.

Celestial holography is relatively new and developing rapidly. We don’t know how the final version will look like. That’s the excitement of research.

Wrap up

A few curious observations suggest that hyperboloidal coordinates are interesting for holography.

- Flat spacetime becomes a stack of hyperbolic disks, with a cylinder representing the global picture.

- The original Ryu-Takayanagi calculations apply to Minkowski spacetime.

- Volume scales as area near the conformal boundary.

- Spacetime hyperboloids are essential in celestial holography.

Are these observations indicative of a profound duality, an underlying realization of the holographic principle for isolated systems in hyperboloidal coordinates? I don’t know. The similarity between Minkowski in hyperboloidal coordinates and AdS is interesting, but it can also be misleading.

The observations here are, by their very nature, coordinate-dependent. Suitable coordinates may ease calculations and suggest research directions, but the results should not depend on them. A significant, coordinate-independent difference to the AdS case is the null conformal boundary of asymptotically flat spacetimes. Any realization of the holographic principle will need to incorporate the null boundary and the associated symmetries as celestial holography is attempting to do.

It can be misleading to take similarities in specific coordinates too far, but it can also be a missed opportunity to ignore them. I think hyperbolic geometry and hyperboloidal surfaces will keep playing an essential role in holography. Watch this space!

There are various subtleties here that I’m glossing over. You can go down the rabbit hole following the Bekenstein bound. ↩︎

Setting the curvature radius to unity for simplicity, $L=1$. ↩︎