Special relativity as hyperbolic geometry

Hyperboloids for relativity and beyond

Space and time bend and stretch with every move.

I was blown away by this as a young high schooler interested in physics and philosophy. To me, the recognition that natural laws dynamically govern space and time was a triumph of physics over philosophy, of Einstein over Kant, of empirical determination over synthetic a priori.

As fascinated as I was by special relativity, the formalism seemed relatively obscure. I recognized patterns in the Lorentz transformations but missed a deeper insight into the origins of this structure. At college, I considered various standard derivations of relativistic effects, such as the relativistic aberration or the Thomas precession, tedious and boring.

A simple example is Einstein’s velocity-addition formula. In Galilean relativity, which corresponds to our everyday experience, we can just add velocities. In special relativity, the speed of light is constant, so the addition of velocities must be such that no composition of velocities exceeds the speed of light. In the simplest case of collinear motion (velocities pointing in the same direction), velocity addition becomes speed addition and looks like this $$ \tag{1} \label{1} u = \frac{u_1+u_2}{1+\tfrac{u_1 u_2}{c^2}} $$ The speed of light, $c$, can never be exceeded with this composition law. While we can understand the result, it is not intuitively clear how this addition rule is related to the structure of space and time.

It turns out that relativistic calculations have natural interpretations in hyperbolic geometry. This viewpoint not only simplifies the calculations but also provides deeper insights into the theory. Its power extends beyond special relativity into machine learning and general relativity. And it all starts with Minkowski.

Hyperbole

In 1908, Minkowski gave a lecture about a new mathematical model for space and time. In his opening remarks, he stated boldly that, from now on, space and time are mere shadows of a more fundamental union: spacetime.

Henceforth space by itself, and time by itself, are doomed to fade away into mere shadows, and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality.

The quote is by now famous. It has made its way to various outlets since appearing on the cover page of Synge’s textbook on relativity in 1956. But when Minkowski made the statement, it was considered hyperbole and encountered resistance from physicists and mathematicians alike.2

The spacetime view became widely celebrated a few years after the lecture because of its central role in general relativity. In the same lecture, Minkowski also promoted a non-Euclidean approach to spacetime. As a Göttingen mathematics professor, he recognized the non-Euclidean geometry of special relativity. This idea, however, didn’t gain traction as widely as the idea of spacetime. Only in the last 20 years has there been renewed interest in the hyperbolic nature of special relativity.

To see why hyperbolic geometry is the natural geometry for special relativity, consider a two-dimensional spacetime with coordinates $(t,x)$ and Minkowski metric

$$ ds^2 = -dt^2 + dx^2. $$

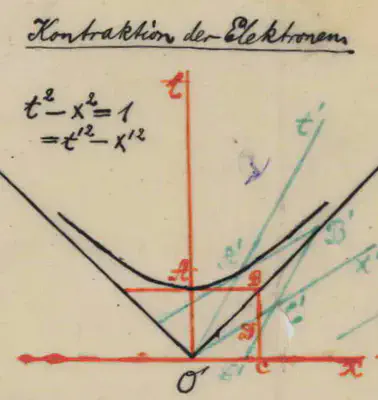

A natural object for a metric is the set of points at unit distance from the origin. In two-dimensional Euclidean space, we get a circle, $x^2+y^2=1$. In two-dimensional Minkowski space, we get a hyperbola

$$ \tag{2}\label{2} t^2 - x^2 = 1. $$

Minkowski’s drawing below shows this hyperbola for $t>0$. In higher dimensions, you get the one-sheeted hyperboloid, also called hyperbolic hyperboloid.

From Minkowski’s modern world by Scott Walter.

In his lecture, Minkowski demonstrated that Lorentz transformations are hyperbolic rotations that leave the hyperbola (\ref{2}) invariant. He died in January 1909 before he could develop this idea further, but it was embraced by a few other scientists, particularly by Sommerfeld, Varičak, Robb, and Borel.

The principle of relativity corresponds to the hypothesis that the kinematic space is a space of constant negative curvature, the space of Lobachevsky and Bolyai. The value of the radius of curvature is the speed of light.

Borel (1913)

The mathematical formalism for a hyperbolic rotation is just like a regular rotation, except with hyperbolic functions instead of trigonometric functions. Hyperbolic functions are related to their trigonometric counterparts through complex angles. An intuitive way to think about the hyperbolic rotation is the squeeze mapping, which should be familiar to anyone who has seen a Lorentz transformation on a spacetime diagram.

From Wikimedia.

Consider the Lorentz boost with relative speed $v$ between frames $$ L(v)= \begin{pmatrix} \gamma & -\gamma \beta \\ -\gamma \beta & \gamma \end{pmatrix}, $$ where we defined the rescaled speed $\beta:=\tfrac{v}{c}$ and the Lorentz factor $\gamma:=1/\sqrt{1-\beta^2}$. We can write it as a hyperbolic rotation with angle $w$: $$ L(w)= \begin{pmatrix} \cosh w & -\sinh w \\ -\sinh w & \cosh w \end{pmatrix}, $$ where the Lorentz factor becomes $\gamma=\cosh w$ and the rescaled speed becomes $\beta=\tanh w$. So the Lorentz transformation is simply a rotation in hyperbolic space with an angle, $w$, related to the observer’s speed as $v=c \ \mathrm{arctanh}\ w$. Its inverse is just a rotation with the inverse angle, $L(w)^{-1}=L(-w)$. We can directly add the hyperbolic angles instead of dealing with weird addition formulas because composition of rotations along the same dimension is additive $L(w_1)L(w_2)=L(w_1+w_2)$.

Physicists usually think in terms of velocities and speeds, not hyperbolic angles. Writing the angle addition in terms of speeds, we get $$ \beta = \tanh (w_1+w_2) = \frac{\tanh w_1+\tanh w_2}{1+\tanh w_1 \tanh w_2} = \frac{\beta_1+\beta_2}{1+\beta_1 \beta_2}. $$ Einstein’s velocity addition (\ref{1}) becomes a consequence of hyperbolic identities.

There is much more that one can simplify or understand with this viewpoint. For example, the formula for the Doppler shift is a simple $e^w$. The non-commutativity of general Lorentz boosts in higher dimensions becomes immediately apparent: Lorentz boosts do not commute just like rotations do not commute. The Thomas precession becomes easier to visualize as the consequence of parallel transport of vectors in the curved velocity space (holonomy transformation). Many other calculations and ideas in special relativity translate to simple exercises in hyperbolic geometry.

If you’re intrigued, follow the rabbit. Scott Walter’s papers are excellent for the historical developments: Hermann Minkowski and the scandal of spacetime, The Non-Euclidean Style of Minkowskian Relativity, and Minkowski’s modern world. There are some gems in Barrett’s The Hyperbolic Theory of Special Relativity. Rhodes and Semon go into those tedious calculations in Relativistic velocity space, Wigner rotation and Thomas precession. Tevian Dray’s textbook on The Geometry of Special Relativity from 2012 takes the hyperbolic viewpoint to teach special relativity.

Ungar probably has the most influential and extensive work in this space. His books on gyrovector space present relativistic calculations in hyperbolic geometry from a solid group-theoretical viewpoint. Two of his relevant books are Analytic Hyperbolic Geometry and Albert Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity from 2008 and Beyond the Einstein Addition Law and its Gyroscopic Thomas Precession from 2012. This work has even found applications in machine learning.

Beyond special

The hyperbolic view opens a new window to a universe beyond rewriting calculations in special relativity.

Hyperbolic geometry efficiently represents hierarchical relationships and complex networks. Nickel and Kiela demonstrated in 2017 that hyperbolic geometry is better than Euclidean geometry when applying machine learning to complex data structures. In a follow-up paper, they compared different hyperbolic models for learning hierarchical relationships and found that the Lorentz model is more efficient than the Poincaré model. Around the same time, Ganea, Bécigneul, and Hofmann derived hyperbolic versions of deep learning tools by using Ungar’s gyrovector formalism.

These papers opened up a new research direction in machine learning on hyperbolic deep neural networks. The researchers use tools developed specifically for special relativity, such as Lorentz transformations and gyrovector spaces, to improve machine learning algorithms. Physicists usually associate velocities and universal speed limits with Lorentz transformations. It is fascinating that Lorentz transformations arise in problems without a notion of motion.

Another application closer to my heart is hyperbolic geometry in general relativity. The spacetime of special relativity is special: we can identify Minkowski space with its tangent space which allows us to talk of spacetime events as four-vectors and apply global Lorentz transformations. These properties do not generalize to arbitrary Lorentzian manifolds. It’s not immediately evident that the hyperbolic viewpoint is still valuable when the spacetime is curved.

As we have seen above, Minkowski’s hyperboloid (\ref{2}) consists of points at unit proper distance from the origin. Hyperboloids are as natural in Minkowski space as spheres are in Euclidean space. So hyperboloidal coordinates may be as natural in Lorentzian manifolds as spherical coordinates are in Riemannian manifolds.

How can we construct such hyperboloidal coordinates? In many applications, we need to separate spacetime into space and time. Let’s separate spacetime into hyperbolic space and time in non-Euclidean style. One approach is to take a hint from spherical coordinates. Generalize the hyperbola from (\ref{2}) to an arbitrary radius of curvature $$ t^2-x^2 = \tau^2, $$ and use $\tau$ as a new coordinate. Setting $x=\tau \ \sinh \rho$ gives us the Milne universe with metric $$ ds^2 = -d\tau^2 + \tau^2 d\xi^2.$$ These coordinates have various use cases today, including quantum field theory, holography, and the theory of partial differential equations.

Another approach is to shift the hyperbola (\ref{2}) along the time direction by $\tau$ recognizing the special role of time $$ (\tau - t)^2 - x^2 = 1 $$ Using $\tau$ as the new time coordinate, the Minkowski metric becomes $$ ds^2 = -d\tau^2 + \frac{2x}{\sqrt{1+x^2}} d\tau dx + \frac{1}{1+x^2} dx^2.$$ Level sets of $\tau$ are hyperbolic spaces. We can bring the metric into the more recognizable Poincaré form by the spatial transformation $x=2 \rho/(1-\rho^2)$. $$ ds^2 = -d\tau^2 + \frac{4}{(1-\rho^2)^2} \left(2\rho d\tau d\rho + d\rho^2\right).$$ This construction generalizes to curved spacetimes. It’s favorable for numerically solving wave equations because the coefficients don’t depend on time. Some of the problems appearing in standard coordinates, such as the outer boundary and radiation extraction problems, don’t arise with this approach because we can solve the wave equation on the infinite spatial domain $\rho\in[0,1]$.

Hyperboloidal coordinates may seem unnatural at first, but that’s because we are used to thinking about space and time in Newtonian terms. Once you spend some time with them, you see that hyperboloidal coordinates are as valuable in Lorentzian manifolds as spherical coordinates are in Riemannian manifolds. I devoted most of my work exploring properties of these surfaces and I find their relation to special relativity fascinating.

Hyperclusion

Physics doesn’t care about how we make calculations in special relativity. The Wikipedia page for the history of Lorentz transformations lists many equivalent formalisms. We could keep the usual relativistic formulas using velocities and Lorentz factors, or employ Bondi’s $k$-calculus, or Ungar’s gyrovector space. Why choose one over the other?

It may be just personal preference. How do you understand? I understand by analogy, so it’s helpful to me when formalisms lend themselves to connections to other fields.

There is another, much more relevant reason to prefer the hyperbolic viewpoint. As scientists, we want powerful descriptions. The same thinking style should apply to a broad class of phenomena. In other words, we want to avoid overfitting our formalism to the phenomena at hand. Hyperbolic calculations translate into machine learning, spacetime curvature, and maybe other areas to be discovered. The non-Euclidean approach with hyperbolic angles seems more powerful than the usual approach with velocities.

The lecture was given on September 21, 1908 in Köln during a meeting of researchers of nature (the lovely German compound word for such a meeting is Naturforscherversammlung). The German version sounds stronger in its proclamation: “Von Stund’ an sollen Raum für sich und Zeit für sich völlig zu Schatten herabsinken und nur noch eine Art Union der beiden soll Selbständigkeit bewahren.” ↩︎

Walter, Scott. “Hermann Minkowski and the scandal of spacetime.” ESI News 3.1 (2008): 6-8. ↩︎