Defining quantum mechanics

It’s not about scale.

The problem with the standard definition

Wikipedia defines quantum mechanics (QM) as “a fundamental theory that describes the behavior of nature at and below the scale of atoms.” Britannica defines it as the “science dealing with the behavior of matter and light on the atomic and subatomic scale.” Many other sources and textbooks define QM as the physics of the very small.

The problem with this definition is simple: it’s wrong.

Macroscopic quantum systems

We cannot define QM as the physics of the very small because there are macroscopic systems that show quantum behavior. When I was studying theoretical physics in Vienna, one of the hottest topics of discussion was Zeilinger’s experiment demonstrating the wave–particle duality of C$_{60}$ molecules. Zeilinger, who received the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics for his research on quantum entanglement, was pushing the limits of quantum behavior. A molecule of 60 carbon atoms is enormous compared to inhabitants of the subatomic scale, such as electrons and photons typically used to demonstrate interferometry. The lead author of the C$_{60}$-paper, Markus Arndt, pushed the limit further, demonstrating quantum interference for large organic molecules. In one experiment, they put molecules consisting of 2,000 atoms into quantum superposition.

There is no theoretical limit to the scale where quantum behavior occurs. If there were, we wouldn’t have a multi-billion dollar industry and a global quantum race trying to build the largest quantum computer.

It’s well-known that macroscopic quantum systems exist. There is even a Wikipedia page on macroscopic quantum phenomena. The best-known examples are superconductors and superfluids.

In a superconductor, pairs of electrons (Cooper pairs) occupy the same quantum state described by a single, coherent quantum wavefunction extending over macroscopic distances. Superconducting magnets in MRI machines or in particle accelerators are big (meters to kilometers) and heavy (tons).

In a superfluid, the particles share a single quantum wave function. Laboratory superfluids are relatively small but there are applications where several hundreds of superfluid helium are used.

The most obviously macroscopic quantum objects are astrophysical. Neutron stars weigh more than the Sun. The nucleons in a neutron star form Cooper pairs leading to superfluidity and superconductivity.

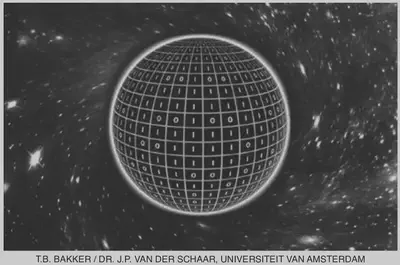

Most impressively, black holes exhibit quantum behavior. The Bekenstein-Hawking entropy, $S_{BH}$, of a black hole is given as the event horizon surface area, $A$, counted in units of Planck area, $\ell_P^2$, $$ S_{BH} = \frac{A}{\ell_P^2} \frac{k_B}{4}, \qquad \mathrm{where} \qquad \ell_P^2 = \frac{\hbar G}{c^3}. $$ Given that entropy measures information, this equation suggests that a black hole functions as a quantum device, storing the information about the matter and energy that have fallen into it. Black holes saturate the theoretical storage limit of quantum information for a region of space.

Black holes can be as large as our entire solar system with billions of solar masses. Clearly, the definition of quantum mechanics as the physics of the very small does not apply here.

Other attempts at a better definition

A definition that’s not blatantly wrong is given in the “Introduction to quantum mechanics” by David Morin

Quantum mechanics can be thought of roughly as the study of physics on very small length scales, although there are also certain macroscopic systems it directly applies to. The descriptor “quantum” arises because in contrast with classical mechanics, certain quantities take on only discrete values. However, some quantities still take on continuous values.

Indeed, we can roughly think of QM as the study of physics on very small scales with the caveats given. But the caveats are confusing. We’re invited to think of QM as the physics of the very small but learn that it also applies to macroscopic systems. Some quantities are discrete, hence the name quantum, but others are continuous. What is it then?

It’s more descriptive to define quantum mechanics through the behavior of quantum objects, such as superposition, entanglement, decoherence, and wave-particle duality1. Unfortunately, this definition smells of a tautology: quantum is what acts quantum. One would like to know when these quantum behaviors arise in contrast to the classical world we’re used to. How should we relate our understanding of the classical world to the magical realm of quantumania?

A better definition

A good definition should outline a rough boundary between classical and quantum behavior. Historically, we discovered quantum mechanics by studying the mechanics of small things like atoms and photons. We now know, however, that the relevant boundary is not scale. It’s environmental coupling.

Quantum mechanics is the study of systems whose environmental coupling is relatively weak.

This definition shifts the focus from scale to the system’s interaction with its environment. It’s a powerful conceptual shift that aligns with modern developments in quantum mechanics. By emphasizing environmental coupling, the definition addresses why certain systems show quantum behavior, regardless of size. One can make the definition more descriptive by including the quantum behaviors we talked about previously:

Quantum mechanics is the study of systems where quantum phenomena, such as superposition, entanglement, and wave-particle duality, are preserved due to relatively weak environmental coupling.

Either way, emphasizing the environmental coupling in the definition instead of the scale is fundamental. Quantum behaviors such as superposition and entanglement arise when the systems are sufficiently isolated from the environment. Environmental coupling results in decoherence and the loss of the quantum state.

Placing environmental coupling at the center of the definition has many benefits. One of the main challenges of building a practical quantum computer is preventing the decoherence of quantum information. That’s why the photos of quantum computers mostly show a giant refrigerator that aims to shield the quantum chip from thermal noise. Reducing environmental coupling of strongly entangled quantum systems is a multi-billion dollar industry.

One approach to deal with environmental coupling is quantum error correction. The idea is to circumvent the no-cloning theorem by storing quantum information in many entangled qubits. When there is some coupling with the environment, the quantum information is preserved as long as the environmental coupling is relatively weak. We will need about a thousand qubits for every logical qubit of a quantum computer.

The definition also gives a first peek into the central relevance of concepts like the measurement problem, entanglement entropy, and density matrices by distinguishing the quantum system from its external environment.

The definition is not perfect2; no definition is. However, I believe it has explanatory power and allows students to understand quantum mechanics better.

This approach is reminischent of Wittgenstein’s famous statement that the meaning of a word is its use in the language. ↩︎

Some subtleties, such as the quantum Zeno effect, remain here. I think the definition works even for this special example because the coupling in the case of the quantum Zeno effect is a projective measurement, which is arguably a relatively weak coupling preserving quantum information. ↩︎